In the world of athletic performance, the difference between good and great often comes down to one critical factor: load management. At Resilience Rehab, we’ve developed comprehensive models for training, rehabilitation, and performance that embrace a simple philosophy – no fluff, just results. This integrated approach addresses everything from breathing and floor work at the foundational level through to high-intensity plyometrics and sport-specific training at the advanced stages. But before we can effectively implement these systems, we need to understand a crucial concept: athletic readiness.

How Readiness Impacts Load Management

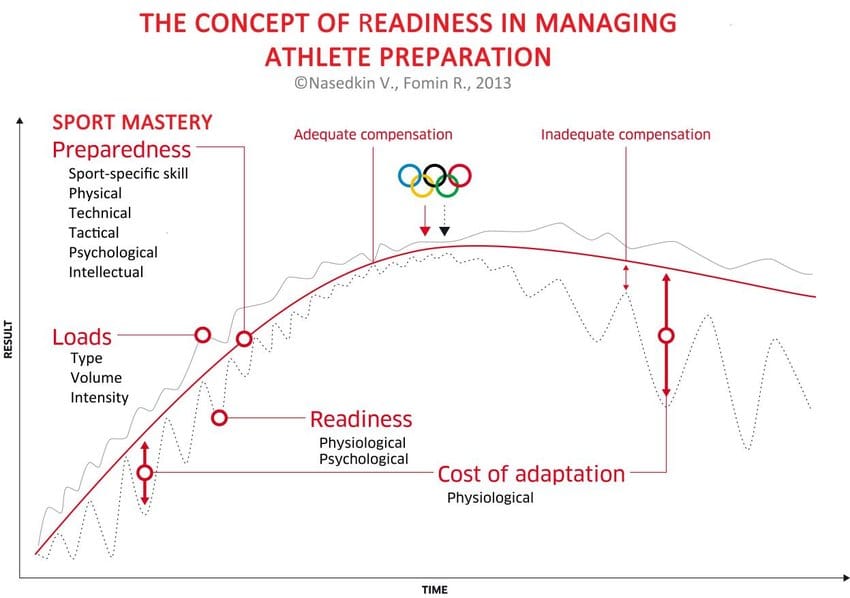

Readiness refers to the fluctuating capacity of the body to tolerate training stress. It represents the gap between what you could potentially do at your peak and what you can currently do based on your present physiological state.

This concept is often illustrated by the stress–adaptation “sweet spot” curve. Too little stress fails to trigger adaptation, while too much stress creates a harmful dose. The optimal zone lies between these two extremes, but importantly, this zone is not fixed. It shifts daily based on multiple internal and external factors.

Optimal performance occurs when stress and recovery are balanced. Along the performance–stress curve, several states can be identified:

- Lame – inactive, disengaged, and under-stimulated (too little stress)

- Healthy – motivated, focused, and appropriately challenged (optimal stress)

- Fatigued – overloaded, exhausted, and under-recovered (too much stress)

- Sick – burnout, breakdown, anxiety, or injury (harmful stress levels)

The key insight is that training capacity fluctuates from day to day. When the gap between potential capacity and current capacity is small, you are fresh, strong, and at lower injury risk. As this gap widens, performance declines and injury risk rises.

Assessing Readiness for Effective Load Management

Readiness assessment must consider multiple physiological systems that contribute to performance and recovery:

- Central nervous system (CNS)

- Autonomic nervous system (ANS)

- Endocrine system

- Neuromuscular system

- Cardiopulmonary system

- Sensorimotor system

- Metabolic systems

Different training stimuli stress these systems in different ways, and recovery timelines vary significantly between individuals. For this reason, the most practical approach prioritises short-term, high-impact systems, knowing that longer-term adaptations tend to follow as a consequence.

In high-performance settings, readiness may be assessed using objective measures such as heart rate variability (HRV), heart rate recovery (HRR), reactive strength index (RSI), jump metrics, or grip strength testing. While useful, these tools are not essential for most people.

For the majority of athletes, a simple daily subjective questionnaire is both practical and effective. Tracking factors such as sleep quality, muscle soreness, energy levels, and overall recovery provides surprisingly reliable insight into readiness.

Rather than chasing a “perfect” score, the goal is to establish personal normal ranges. Persistently low scores suggest training demands are excessive, while consistently high scores may indicate insufficient challenge. The ideal zone is a mix of medium to high readiness scores, reflecting an effective balance between stress and recovery.

Proper Load Management: Planning Your Training

Effective load management begins with a simple question: what adaptation are you trying to create? From there, planning works backwards:

- What physiological environment drives that adaptation?

- What exercises or training conditions create that environment?

- How can those conditions be maintained safely within a session?

This approach blends two complementary ways of thinking.

Top-Down Planning (Outcome-Focused)

- Long-term vision and outcomes

- Assumes predictability

- Analytical and metric-driven

- Often struggles with human variability

Bottom-Up Planning (Process-Focused)

- Minimum viable program

- Starts from current capacity

- Requires an end goal but prioritises present readiness

Outcome goals provide direction but are largely uncontrollable. Performance goals are mostly controllable. Process goals are fully controllable and form the backbone of sustainable progress.

Making Load Management Decisions When Uncertain

When training decisions feel unclear, a conservative bias is often the safest option. Several guiding principles apply:

- Progress can be ruined by adding too much, too soon

- Progress is not harmed by being conservative and building gradually

- Training sessions should finish feeling like more was possible

- No adaptation is worth an excessively high cost

Sustainable improvement comes from consistency, not from chasing maximal sessions. When readiness is high, apply a strong stimulus. When readiness is low, reduce load, maintain capacity, and prioritise recovery.

Load Management in Practice

The Pain Codex planning approach provides a structured framework for managing training blocks with defined phases, focus areas, and progressive objectives. Each phase builds on the previous one while readiness is continually monitored.

This method allows adaptation to occur without accumulating excessive stress, reducing the risk of injury, stagnation, or burnout.

By understanding your body’s fluctuating capacity for stress, assessing readiness consistently, and aligning training load with both process and outcome goals, performance can be optimised while minimising injury risk.